Mycology is the study of fungi and the diseases or infection caused by fungi are known as mycoses. Fungi are aerobic, nucleated, achlorophyllus (lack chlorophyll and implies that most of them are saprophytic organisms which typically reproduce sexually and/or asexually). These organisms usually filamentous, branched somatic structures are surrounded by a thick cell wall containing large amount of chitin (made of N–acetyl glucosamine, is one of the toughest biologically produced materials).

Fungi are classified into seven divisions or phyla, based on the way the fungus reproduces sexually. These divisions include Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Microsporidia and Neocallimastigomycota.

The subsequent use of morphological and biological criteria enables differentiation of the kingdom Fungi into five phyla: Ascomycota (sac fungi), Basidiomycota (club fungi), Mycophycophyta (lichens fungi), Zygomycota (conjugation fungi), and Deuteromycota (imperfect fungi or mitosporic fungi).

More recent adoption of polyphasic approaches

including phylogenetic analysis permits classification of the kingdom Fungi

into two subkingdoms and five phyla: Dikarya (including phyla Ascomycota and

Basidiomycota) and Eomycota (including phyla Zygomycota, Glomeromycota, and

Chytridiomycota) in addition to Microsporidia.

Fungal structure

Hyphae are long, slender, branching tubes and has uniform diameter. If hyphae have crosswalls, the fungus is said to be septate. If crosswalls are not present, the fungus is said to be coenocytic or non-septate. Hyphae might be considered as being the root system of fungi. A mass of hyphae is called mycelium. Mycelium has two parts:

a. Aerial mycelium – the portion of the mycelium that projects above the substrate and produces spores. Because of its capability to produce spores, it is also known as reproductive mycelium.

b. Vegetative mycelium – the portion that penetrates the substrate and absorbs foods.

Hyphae cells have tubular, multicellular forms, which can be induced by a temperature of 37°C, N-acetyl glucosamine, embedding matrix, hypoxia and hypercapnia (increase in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) above 45 mm Hg), alkaline pH in vitro, involvement in biofilm formation, and the ability to grow thigmotropically (sensitivity to touch). Hyphae developed from an ungerminated yeast cell, without constriction in the neck of the mother cell and having parallel sides throughout its length. During the hyphal cell cycle, a septin ring will appear in the daughter cell.

Pseudohyphal cells have long elliptic, multicellular forms, which can be induced at pH 6.0, 35°C, on solid limited nitrogen medium, and via involvement in biofilm formation. In Pseudohyphal cells, there is a constriction at the neck of the bud and mother cell, even at every subsequent septal junction. Pseudohyphae cells can vary widely in width and length so that at one extreme they resemble hyphae, and at the other, they resemble elongated buds of yeast cells. One of the characteristics of pseudohyphae is that the width of each segment that forms the mycelia is not constant, being wider at the center than the two ends. In pseudohyphae, the connection between a mother cell and daughter cell is easily interrupted by mechanical agitation, and this connection is not difficult to interrupt.

β-D-Glucans, which constitute the structural compounds of most fungal cell walls, are known to stimulate macrophages and neutrophils. These compounds are effective markers of surfaces containing fungal clusters on dusty surfaces. Fungal glucans, especially (1,3)-ß-glucans, have been reported to play an essential role as inducers of chronic pulmonary diseases. Glucans may be associated with signs of non-specific inflammation, as well. The water-insoluble form of glucan causes a delayed response in terms of reduced levels of macrophages and lymphocytes in the lung wall.

FUNGAL REPRODUCTION

Spores are the structures set aside by the fungus for reproduction. There are two types of spores:

A. Sexual spores (meiospores) – the mechanism is the same as sexual reproduction, which is an alternation of karyogamy (nuclear fusion) and meiosis (reduction division).

Sexually reproducing fungi may combine by fusing their hyphae together into an interconnected network called anastomosis. Sexual reproduction begins when the haploid hyphae from two fungal organisms meet and join.

a. Ascospores – spores which are formed within a sac or ascus.

The generation of ascospores is a defining feature of the fungal phylum Ascomycota. Ascospores are generally found in clusters of four or eight spores within a single mother cell, the ascus. These spores are formed as a means of packaging post meiotic nuclei. As such, they represent the “gametic” stage of the life cycle in these fungi. The creation of these specialized cells requires a cell division mechanism distinct from that used during vegetative growth of fungal cells.

b. Basidiospores – spores which are formed on the surface of a basidium.

They are formed on sterigma on each cell of the basidium. The spores are actively discharged a few centimeters from the sterigma at maturity. Basidiospores are small, hyaline, and oval-shaped. They can develop and are released within 20–25 min after the teliospore is moistened. However, some viable teliospores may not germinate for 3–6 or more days.

c. Oospores – spores which are formed by the union of two sexually undifferentiated cells. This happens when an oogonium (female gamete) is fertilized by an antheridial (male gamete) nucleus; a characteristically thick wall and food reserves help to ensure survival.

d. Zygospore – a thick-walled resting spore produced in a zygosporangium after fusion of two gametangia.

The sexual cycle starts when mycelia of the two mating types, often called sexes, meet on a solid surface. The most apparent result is the formation of zygospores, large cells with thousands of nuclei of both parents. Zygospores rest for at least 2 months and then germinate in relative synchrony, that is, within about 1 month, without the need to be fed anything but water. Each zygospore produces a macrophore, which is very similar to those of the asexual cycle and develops a germsporangium with germspores. Germspores are multinucleated, but, unlike vegetative spores, derive from uninucleated primordia.

|

SEXUAL

SPORES OF FUNGI |

|||

|

Ascospore |

Basidiospore |

Oospore |

Zygospore |

B. Asexual spores (mitospores) or asexual reproduction occurs strictly by the process of mitosis. This is the most common process by which spores are produced in fungi.

a. Thallospores – produced from the cells of thallus or body of the fungi. The thallus of most true fungi is haploid (contains one set of chromosomes); thus, the diploid (two sets of chromosomes) zygote that results from karyogamy must undergo meiosis before a haploid thallus can then develop.

1. Arthrospores or oidia – spores resulting from hypha fragmenting into individual rectangular cells.

2. Chlamydospores – large, round, thick walled, unicellular structure formed by the enlargement of the hyphal element. Chlamydospores generally function as resting spores and are formed under unfavorable environmental or nutritional conditions.

b. Conidiospores – formed on specialized hyphae. Conidiophores or sporangiophores are asexual structures that produce propagules by division or redistribution of nuclei without nuclear fusion.

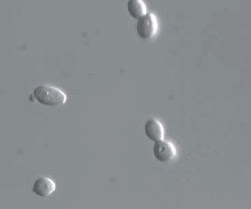

1. Blastospores – a vegetative fungal cell that forms by budding from hyphae. Example is Candida albicans.

2. Porospore – a conidium which develops through a pore in the wall of condiophore.

3. Aleuriospores or Gangliospores – a spore produced terminally by septation but remaining attached until disintegration of the mycelium. Example is Paracoccidioides brasiliensis.

4. Phialospores – are flask shaped spore which continuously elongates at the tip but from which conidia are successively cut off, so that the length of the cell remains constant. Example is Aspergillus.

Conidiogenesis is the formation of asexual spores (conidia or conidiospores). A conidiophore is simple or branched hypha on which conidia are produced. Conidia can be one-celled, two-celled, or multicellular with transverse or oblique septa. They have different shapes, appearing filiform (thread-like), ovoid (egg-shaped), clavate (club-shaped), stellate (star-like), cylindrical or branched. They may be pigmented or have appendages. Conidia can also be large and multicellular as in Macroconidia or small and unicellular as in Microconidia.

The modes of conidium formation includes:

1. Thallic development – the conidial initial does not enlarge before it separates from the conidiophore.

2. Holoblastic development – all cell wall layers expand during conidium formation.

3. Enteroblastic development – only the inner layer of the cell wall expands through an aperture in the outer wall of the conidiophore.

4. Phialidic development – conidium is formed by the synthesis of new cell wall material within the neck of the phialide which can produce masses of conidia in dry chains or conglomerates.

Mitosporic fungi are divided into three informal classes:

1. Coelomycetes – spores are produced in fruiting structures called conidiomata. Coelomycetes are characterized by the production of conidia that form in some type of cavity in the host tissue.

Coelomycetes produce conidia in fruiting structures such as pycnidia (a flask-shaped structure lined on the inside with conidiophores) and acervuli (conidiophores lay side by side in a flat, saucer-shaped configuration) embedded in host tissue.

2. Hyphomycetes – spores are produced on separate conidiophores (hyphae). The hyphomycete class of fungi represents endophytic fungi that produce asexual spores (Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Alternaria) and are well known to produce diverse anticancer metabolites. The term “endophytic fungi” refers to fungi that live in plant tissues throughout the entire or partial life cycle by establishing a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship with its host plant without causing any adverse effect or disease.

Conidia within the hyphomycetes have distinct conidiophores and are produced singly, as synnema (a group of conidiophores are united together to form a stalk), or as sporodochia (clusters of conidiophores that form a cushion of hyphae on the host surface).

3. Agonomycetes (mycelia sterilia) – are fungi which usually produce neither sexual (meiotic) nor asexual (mitotic) spores.

Some fungal anamorphs have no known sexual state in their life cycle and thus remain unclassified. These organisms, also known as mitosporic fungi, are placed in an artificial group called the Deuteromycota or the Fungi Imperfecti. They reproduce mitotically via conidia.

DIFFERENT CLASSIFICATION OF FUNGI

Different forms of Fungi:

1. Monomorphic Fungi – fungi that exists in either yeast or mold form.

a. Yeast are unicellular organisms which multiply by budding and are characterized by the absence of mycelium. An example is Cryptococcus neoformans.

b. Mold grows by apical extension of their filaments, known as hyphae (singular = hypha). Molds are long filamentous branching organisms which may be septate (e.g., Aspergillus) or aseptate/pauciseptate (e.g., Mucormycetes). The molds can also be classified into two broad groups, the phaeohyphomycetes and the hyalohyphomycetes, based on color of the fungi. The phaeohyphomycetes are black and hyalohyphomycetes are hyaline.

Examples include: Piedraia hortae, Hortaea werneckii, Microsporum species, Trichophyton species, Epidermophyton species, Aspergillus fumigatus, Cladosporium carrionii, Fonsecaea compacta, Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, Pseudallescheria boydii, Madurella grisea, Madurella mycetomata, Exophiala jeanselmei, Actinomyces israelii, Actinomyces bovis, Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia brasiliensis, Coccidioides immitis.

2. Dimorphic Fungi – grow as yeasts or spherules in vivo, as well as in vitro at 37°C, but as molds at 25°C. Dimorphic fungi are highly infectious. As a result, this group of primary pathogens is classified as Biosafety Level (BSL) 3 organisms. At a minimum, processing of clinical specimens for fungal culture should be done in a BSL 2 facility under a class II biosafety cabinet and when dimorphic fungi are suspected, all isolates should be maintained on slants to prevent aerosolization. When grown in culture in filamentous forms, BSL-3 practices should be used when manipulation of isolates is required.

Examples of dimorphic fungi include: Sporothrix schenckii, Blastomyces species, Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Penicillium marneffei (divide by fission).

3. Pleomorphic Fungi – are fungi that exhibit both sexual and asexual reproduction. The sexual state of a fungus is called the teleomorph (often referred to as the perfect state), and the asexual state is called the anamorph (the imperfect state). The organism in its totality (both anamorph and teleomorph) is the holomorph.

Classification of fungi by morphologic features in tissues:

The classifying features include pigmentation, hyphal diameter, and frequency of septation.

1. Phaeohyphomycosis – pigmented hyphal or yeast forms.

2. Hyalohyphomycosis – nonpigmented hyphal forms.

3. Eumycotic mycetoma – fibrosing granuloma with black or white tissue grains consisting of aggregates of pigmented or nonpigmented fungi, respectively.

4. Zygomycosis – wide, infrequently septate, nonpigmented hyphae associated with pyogranulomatous and eosinophilic inflammation.

Classification of fungi by Phylum

1. Pseudomycetes – false fungi or fungal–like organism.

a. Schizomycetes – an obsolete term for "fission fungi" or bacterial cells that do not contain a nucleus and rarely harbor membrane-bound organelles.

(1) Actinomycetes – Actinomyces israelii, Actinomyces bovis, Actinomyces naeslundii.

(2) Nocardia – Nocardia asteroides, Nocardia madurae, Nocardia tenuis, Nocardia minutissima, Nocardia pelletieri, Nocardia paraguayensis, Nocardia brasiliensis.

b. Myxomycetes – also known as slime molds or myxogastrids. A group within the Amoebozoa well known for their motile plasmodia (instead of mycelia) and morphologically complex fruiting bodies. Pythium insidiosum is the known fungi that causes human infection.

2. Eumycota – true fungi or Eumycetes. They form extended mycelia and have a diverse asexual and sexual spore structure.

|

CLASSIFICATION

BY MYCELIUM TYPE |

||

|

Classification |

Sexual |

Asexual |

|

a.

Aseptate mycelium |

||

|

(1)

Mucorales |

Zygospores |

Sporangiospores |

|

(2)

Entomophthorales |

Conidia |

|

|

b.

Septate mycelium |

||

|

(1)

Ascomycetes |

Ascospores |

Conidia |

|

(2)

Basidiomycetes |

Basidiospores |

Blastospores |

|

Conidia |

||

|

(3)

Deuteromycetes

(Fungi imperfecti) |

None |

Blastospores |

|

Chlamydospores |

||

THE MUCORALES

The Mucorales fungi together with the Entomophthorales fungi was previously classified under Phylum Zygomycota or Zygomycetes (Phycomycetes). However, the phylum Zygomycota was abandoned because it was not supported in molecular phylogenies that included a higher number of loci and taxa.

As a consequence of the phylogenetic distance and taxonomic separation of the Mucorales and the Entomophthorales, the term “zygomycosis’’ (infections caused by members of the Zygomycota) was abandoned and instead the term ‘‘mucormycosis’’ was used for infections caused by members of the Mucorales and “entomophthoromycosis” was used for infections caused by members of the Entomophthorales.

The term “coenocytic hyphomycosis” is proposed to summarize all fungal infections caused by Mucorales and species of Basidiobolus and Conidiobolus.

Mucorales is commonly known as “early diverging fungi” because they are in a basal position with respect to Basidiomycota and Ascomycota in the fungal tree of life.

Clinical feature:

1. Rhinocerebral disease represents one-third to one-half of all cases of zygomycosis. Pulmonary disease is also a common manifestation with this group of organisms. Leukemia, lymphoma, and diabetes mellitus underlie the majority of cases with primary pulmonary involvement. Growth of the fungus in a preexisting lesion produces an acute inflammatory response with pus, abscess formation, tissue swelling, and necrosis. The lesions may appear red and indurated but often progress to form black eschars. Necrotic tissue may slough off and produce large ulcers.

2. Infections are caused by inhaling spores followed by the formation of invasive hyphal structures, subsequent invasion, and obstruction in blood vessels in support of the hematogenous spread.

3. Mucorales species are vasotropic, with the hyphae invading blood vessels during infection and causing tissue infarctions and necrosis. Elevated serum free iron increases the possibility of infection with mucormycosis.

4. Angioinvasion is a hallmark of mucormycosis. Angioinvasion or vascular invasion refers to the invasion of tumor cells into the blood or lymphatic vessels, which is closely correlated with tumor aggressiveness and the potential for metastasis.

5. Rhizopus, Mucor and Lichtheimia (formerly Absidia) are the most common genera causing mucormysosis, accounting for 70–80% of all cases, whereas Cunninghamella, Apophysomyces, Saksenaea, Rhizomucor, Cokeromyces, Actinomucor and Syncephalastrum are responsible for <1–5% of reported cases.

6. They are economically important as fermenting agents of soybean products and producers of enzymes, but also as plant parasites and spoilage organisms.

7. Mucorales may also be parasitic and predaceous, especially in regard to causing disease in humans and animals. In all cases, the fungi absorb their nutrients rather than synthesizing them. They require no light for growth.

|

CLINICALLY

RELEVANT SPECIES OF MUCORALES |

||

|

Actinomucor elegans |

Lichtheimia ramosa |

Mucor velutinosus |

|

Apophysomyces elegans |

Mucor amphibiorum |

Rhizomucor miehei |

|

Apophysomyces mexicanus |

Mucor ardhlaengiktus |

Rhizomucor pusillus |

|

Apophysomyces ossiformis |

Mucor circinelloides |

Rhizopus arrhizus (incl. var. delemar) |

|

Apophysomyces trapeziformis |

Mucor griseocyanus |

Rhizopus homothallicus |

|

Apophysomyces variabilis |

Mucor indicus |

Rhizopus microsporus |

|

Cokeromyces recurvatus |

Mucor irregularis |

Rhizopus schipperae |

|

Cunninghamella bertholletiae |

Mucor janssenii |

Saksenaea erythrospora |

|

Cunninghamella blakesleeana |

Mucor lusitanicus |

Saksenaea loutrophoriformis |

|

Cunninghamella echinulate |

Mucor plumbeus |

Saksenaea trapezispora |

|

Cunninghamella elegans |

Mucor racemosus |

Saksenaea vasiformis |

|

Lichtheimia corymbifera |

Mucor ramosissimus |

Syncephalastrum racemosum |

|

Lichtheimia ornata |

Mucor variicolumellatus |

Thamnostylum lucknowense |

Cultural and Microscopic characteristics:

1. Mucorales present specific features such as coenocytic hyphae and a cell wall containing polysaccharide chitosan (an N-deacetylated version of chitin), whereas other distant groups of fungi like Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes have septate hyphae with chitin as the main polysaccharide.

2. The predominant human pathogen of the Mucorales is Rhizopus arrhizus (aka Rhizopus oryzae). It may be recognized by its very rapid growth on standard media, producing colonies about 1 cm tall.

3. Unique for the order Mucorales is columella, which is a noticeable sterile mid-vesicle within the sporangium and becomes prominent after the liberation of the spores. They produce pigment less, broad (having an irregular diameter of approximately 5–20 μm), slender-walled, ribbon-shaped hyphae along with a small number of occasional septae (also called pauciseptate) and right-angled branches.

4. In Mucor species, anaerobiosis and the presence of a fermentable hexose induce yeast growth, whereas oxygen and nutrient limitation conditions lead to hyphal growth.

|

DIFFERENTIATING

FEATURES OF MUCORMYCOSIS |

|||

|

Fungal

Elements |

Mucormycosis |

Aspergillus |

Candida |

|

Width |

15–20

μm |

4–5

μm |

2–3

μm |

|

Septations |

Aseptate |

Septate |

Septate |

|

Branching |

90o

angle |

45o

angle |

|

|

DISTINGUISHING

FEATURES BETWEEN MUCORALES AND ENTOMOPHTHORALES |

||

|

Characteristics |

Mucorales |

Entomophthorales |

|

Geographic distribution of organisms |

Most but not all species distributed worldwide |

Worldwide distribution, but endemic in tropical

climates |

|

Geographic distribution of cases |

Most species cause infections worldwide |

Predominantly seen in tropical and subtropical

regions |

|

Mode of transmission |

Majority of infections result from inhalation of spores

or traumatic implantation |

Majority of infections result from inhalation of

spores, traumatic implantation, bug bites, or other percutaneous mechanisms |

|

Host immune status |

Predominantly immunocompromised, but some

competent hosts also seen |

Predominantly immunocompetent, only a few

compromised hosts |

|

Most common disease manifestations |

Pulmonary disease most common; rhinocerebral,

cutaneous/subcutaneous, gastric, and other forms also seen |

Sinusitis disease predominates for Conidiobolus

coronatus, while subcutaneous mycosis predominates for Basidiobolus ranarum |

|

Invasive qualities |

Primarily angioinvasive |

Most infections are localized, demonstrating no

angioinvasion |

|

Organism colony morphology |

Floccose aerial mycelium; often seen as “lid

lifters” |

Waxy, folded, and compact mycelium |

|

Organism mycelium morphology |

Coenocytic hyphae, predominantly aseptate;

Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon rarely seen |

Coenocytic hyphae, becoming moderately septate

with age; Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon characteristically seen in tissue

sections |

THE ENTOMOPHTHORALES

Entomophthoraleans are fast-growing fungi forming spores by developing abundant forcibly discharged sticky conidia. They are considered primary or secondary mesotrophic colonizers of difficult-to-degrade substrates, such as cellulose, suberin, chitin, and others. Their physiological characteristics and biochemical properties (e.g., the production of chitinolytic and saccharolytic enzymes) make them successful competitors among fungi and common inhabitants of soil and organic debris. Some Conidiobolus species can develop within living insects and mites (e.g., Conidiobolus coronatus). Basidiobolus species had been found in the gastrointestinal tract of amphibians and reptiles and are readily recovered in their feces. These species are characterized by the development of complex conidium systems to facilitate their spread in nature. Entomophthoralean species are also parasites of nematodes, arthropods, and insects.

The Entomophthorales produce colony morphologies distinct from those of the Mucorales. This class of molds is characterized by the production of a compact mycelium that actively expels asexually produced spores. Basidiobolus species produce waxy, glabrous, and furrowed colonies, which may be pigmented. Conidiobolus species produce colonies that are at first waxy but become powdery with age. Expelled spores may affix to the petri dish lid or tube wall or may land on adjacent medium to produce characteristic satellite colonies.

Pathogens in the Entomophthorales have a range of spore types; ballistospores are shot off, by sudden pressure release, but if they fail to hit a suitable target, sticky secondary spores emerge from the ballistospores.

Entomophthoromycosis Infection:

Entomophthoromycosis are infections caused by Basidiobolus and Conidiobolus species. The main species causing basidiobolomycosis is Basidiobolus ranarum, but cases of Basidiobolus meristosporus, Basidiobolus omanensis, and Basidiobolus haptosporus have also been reported. Conidiobolomycosis is caused by Conidiobolus coronatus, Conidiobolus pachyzygosporus, Conidiobolus lamprauges, and Conidiobolus incongruus.

Chronic localized fibrosing leukocytoclastic vasculitis (CLFLCV) was recently suggested as a factor in cases of entomophthoramycosis of the face. According to the CLFLCV hypothesis, long-standing lymphostasis could induce permanent tissue overgrowth, as in elephantiasis cases. One of the main clinical features of infections caused by these species in humans is their preference for the subcutaneous tissues of the face.

1. Basidiobolomycosis

a. Basidiobolomycosis is caused by Basidiobolus ranarum. This organism resides in decaying plant material, soil, leaves from deciduous trees, and the intestines of fish, frogs, toads, insects, reptiles, and insectivorous bats. The disease is more common in children. Clinically, there is involvement of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, characterized by the formation of fluctuant, firm, and nontender swellings. The overlying skin is usually normal, and there is no bone involvement. Lymph node or muscle involvement can rarely occur. Cases of both gastrointestinal infection and disseminated basidiobolomycosis affecting immunocompetent hosts have been reported. The disease is characterized by the development of swelling erythematous nodular lesions with a “bathing suit” distribution around the buttocks, thighs, and limbs.

b. Common clinical symptoms related to intestinal basidiobolomycosis include (i) bloody, mucous diarrhea; (ii) epigastric abdominal pain; (iii) intermittent low fever; (iv) intestinal bleeding; (v) vomiting; and (vi) the development of tumor-like masses involving the stomach and intestinal tissues.

2. Conidiobolomycosis

a. Rhinofacial conidiobolomycosis is characterized by lesions that originate in the inferior turbinate and spread through ostia and foramina to involve the facial and subcutaneous tissues and paranasal sinuses. Most cases have been described from areas of tropical rainforest in West Africa, with agricultural and outdoor workers (aged 20 to 60 years) being the ones most commonly affected. The fungus is found in soil and decaying vegetation. Patients usually present with unilateral nasal obstruction, nasal discharge, epistaxis, sinus tenderness, and swelling of the nose, upper lip, and face. The disease usually involves the subcutaneous tissue either as a granulomatous infection without bone destruction or as an ulcerated skin lesion, and the clinical course is slowly progressive. Disseminated infections, including those with fatal outcomes, have been reported with Conidiobolus coronatus in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Conidiobolus incongruus is a rare agent of the disease.

|

DIFFERENCE

BETWEEN ENTOMOPHTHORALES SPECIE |

||

|

Characteristic |

Conidiobolus

specie |

Basidiobolus

specie |

|

Environmental microbiology |

Soil, decaying plant material, sheep, horses,

insects and faces of amphibians |

Insects, wood lice, decaying vegetation, feces of

amphibians, horses, dogs, bats, and humans |

|

Pathogenesis |

Acquisition via inhalation of spores, minor trauma

and iatrogenically. Virulence factors include elastase, esterase, collagenase,

and lipase. Host defense includes macrophages with epithelioid and

multinucleate giant cell formations, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and

eosinophils. |

Transmission via minor trauma, insect bites and

iatrogenically. Virulence factors include protease and lipase. Host defense

includes macrophages with epithelioid and multinucleate giant cell

formations, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. |

|

Clinical manifestations |

Facial deformity, fixed subcutaneous nodules,

lymphadenopathy, cellulitis, periorbital swelling, visual impairment,

headaches |

Mobile subcutaneous nodules, lymphedema,

hyperpigmentation and ulceration of skin, constipation, rectal bleeding |

|

Principal sites of infection |

Rhinofacial |

Limbs, buttocks, back, thorax, lung, and

gastrointestinal tract |

|

Types of lesions |

Begins as soft tissue swelling that progresses to

subcutaneous nodule formation. Lesion can become destructive as it spreads |

Subcutaneous tumorlike masses that may cause

ulcerative lesions on skin |

|

Disseminated disease |

Intracranial, mediastinum, kidney, liver, and

gastrointestinal tract |

Dissemination is less frequent |

|

Pathology |

Chronic inflammation and tissue destruction with

spread of lesion. Demonstrate Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon |

Chronic inflammation and enlargement of lesion.

Demonstrate Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon |

|

Clinical mycology |

On culture, glabrous, flat beige to brown colonies

that later develop white aerial hyphae. Plate and tube become covered with

spores discharged from short, nonbranching sporangiophores that have distinct

papilla. Spores may have hairlike, villous projections. |

On culture broad, thin-walled, ribbonlike hyphae

that form gray to beige glabrous, waxy colonies. Plate and tube become

covered with club shaped spores with knoblike tip that are forcibly

discharged from sporangiophores. |

|

Treatment |

Amphotericin B, voriconazole, ketoconazole,

posaconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and potassium iodide. Surgical

management early in course of nasofacial disease. Hyperbaric oxygen. |

Fluconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole,

itraconazole, potassium iodide, trimethoprime-sulfamethoxazole. Surgical

resection of gastrointestinal lesions. Hyperbaric oxygen. |

|

Common

clinical findings in individuals with subcutaneous, intestinal, or systemic

Basidiobolomycosis / Conidiobolomycosis |

||||

|

Species |

Infection

of the face |

Systemic

infection |

Subcutaneous

infection other than the face |

Intestinal

infection |

|

Conidiobolus

coronatus |

Reported

in apparently healthy individuals; clinical signs of early infection include

serosanguinous nasal discharge and single or multiple nasal granulomas

leading to nasal passage blockage; slowly growing granulomas involving

adjacent tissue of the face including lips, mouth, sinus, nasopharynx, and

others |

Some

cases in immunocompromised and organ transplant patients; fever, anorexia,

pleuritic and chest pain, fever, severe weight loss with lung involvement,

and dissemination to blood vessels and brain are the main findings. |

Unusual

cases involving subcutaneous tissues in anatomical areas other than the face

have been reported. |

There

is a rare report without culture suggesting disseminating infection due to Conidiobolus

coronatus from the face to liver, kidney, and small intestine. |

|

Conidiobolus

incongruus |

Cases

in humans are rare; patients with this infection showed refractory fever,

cellulitis of the forehead with sinusitis, obstruction of the nares,

periorbital edema, and orbital inflammation. |

Systemic

infections are common in immunocompromised hosts; involvement of the lungs

was a common feature in these patients; anorexia, persistent cough with or

without hemoptysis, fever, and weight loss; invasion of internal organs,

including liver and lymph nodes. |

A

case affecting the right foot in a diabetic female was diagnosed; the

clinical description lacks details, but pain of the right foot with

violaceous swelling and ulcers was noted |

An

unusual case involving the small intestine (jejunum) was reported; the

infection started as a subcutaneous infection and spread to other organs,

including intestine |

|

Conidiobolus

lamprauges |

No

human cases involving the face have been reported; however, in sheep, the

main affected areas are the face and nasal passages with eosinophilia and the

Splendore-Höeppli reaction. |

Only

one report of a 61-yr-old lymphoma patient has been documented; the patient

developed severe pulmonary infection and expired soon after diagnosis; at

autopsy, C. lamprauges was found in bladder, blood vessels, heart, kidney,

lungs, spleen, thyroid gland, and urethra |

Yet

to be reported |

Yet

to be reported |

|

Basidiobolus

ranarum |

A

5-yr-old boy was diagnosed with a large swelling involving the right side of

the face; the granuloma extended to the submandibular and retroauricular

areas; a usual case involving the eye causing endophthalmitis was also

recorded in India. |

Rare

infection among cases of intestinal basidiobolomycosis; usually, patients

with intestinal infection with dissemination to liver, small bowel,

gallbladder, pancreas, kidney, or retroperitoneum have been reported;

pulmonary infection spread from a cutaneous lesion was also recorded. |

Reported

to occur in apparently healthy hosts; lesions are painless and found around

the neck, trunk, limbs, buttocks, and, less frequently, other sites; usually,

edematous extensive single granulomatous lesions are observed; in the

infected areas, there is moderate to severe pruritus around nodular lesions

with eroded to ulcerative granulomas. |

Reported

to occur in apparently healthy individuals; common clinical signs include

abdominal pain, abdominal distention, constipation, fever, vomiting, weight lost,

rectal bleeding, hepatomegaly, perianal swelling, and palpable abdominal

masses; these masses can be visualized in colon and rectum using CTa. |

THE ASCOMYCOTA

All members of Class Ascomycota that reproduce sexually produce an ascus (from the Greek “askos,” meaning sac), containing spores. Ascus, a sac-shaped structure that contains ascospores, the product of meiosis during the sexual reproductive process. Asci are formed when the female sex cell (ascogonium) is fertilized by the male gamete (antheridium). The diploid zygote nucleus undergoes meiosis followed by one mitotic division to form eight ascospores, which remain in the sac until they are discharged and disseminated. No motile zoospores are produced.

Ascomycetes are utilized in industrial applications, in food production and flavoring, and the fruit bodies of morels and truffles are prized edible fungi.

Asci are unitunicate (with a single wall) or bitunicate (with a double wall). For most ascomycetes, asci are produced in fruiting structures called ascomata (or ascocarps). The different types of ascomata are the:

1. Apothecium – open, cup-shaped with exposed unitunicate asci.

2. Cleistothecium – completely closed, lined with one or more unitunicate ascus.

3. Perithecium – flask-shaped with an opening, or ostiole, at the tip, lined with unitunicate asci.

4. Pseudothecium or ascostroma – bitunicate asci are produced in a cavity or locule buried within a stroma of fungal mycelium.

Asexual reproduction in ascomycetes is most common as conidia produced on conidiophores; other forms include chlamydospores and reproduction by budding or fission (yeasts).

Unfortunately for taxonomists, many members of Class Ascomycota simply do not reproduce sexually; hence, they do not produce the ascus that characterizes their taxonomic class. Taxonomists invented a temporary class of organisms known as the deuteromycotes (or imperfect fungi) to hold these asexual species.

There has been continuing taxonomic confusion over classification of Ascomycetes of the teleomorphic (sexual) stages and the anamorphic (asexual) conidial stage when they are not produced by a single occurrence.

Currently, three major classes account for all the pathogenic members of Class Ascomycota:

1. Class Pezizomycotina contains most of the Ascomycotes and is distinguished from the other by the presence of Woronin bodies.

Several soil-inhabiting members of the ascomycete order Onygenales have evolved to parasitize mammals and cause systemic infection. They have been classified in the family Ajellomycetaceae, which include Blastomyces dermatitidis (teleomorph, Ajellomyces dermatitidis), Histoplasma capsulatum (teleomorph, Ajellomyces capsulatus), Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Paracoccidioides lutzii, Lacazia loboi, Coccidioides immitis, Coccidioides posadasii, and related fungi with similar properties. Also, fungi from Order Onygenales are highly susceptible to fungicide benomyl.

Some dermatophytes, mostly the zoophilic and geophilic species of Microsporum and Trichophyton, are also capable of reproducing sexually and producing ascomata with asci and ascospores. These species are classified in the “teleomorphic” genus Arthroderma together with genus Nannizzia. On the other hand, the “anamorphic” genus of some dermatophytes is placed under the Deuteromycetes, in the order Moniliales.

Other pathogenic species include: Aspergillus (Eurotiomycetes), Piedraia (Dothideomycetes ) and Madurella (Sordariomycetes).

All thermally dimorphic fungi are members of the order Onygenales, except for Sporothrix species that belong to the phylogenetically distant order Ophiostomatales.

2. Class Saccharomycotina are yeasts; round, unicellular fungi that reproduce by budding. This class contains a single genus that is pathogenic in humans: Candida.

Some ascomycetes are responsible for food spoilage; others are used in fermentations, especially species of yeasts. The major fermentative yeasts are strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae used to make bread, beer, saké, wine and many other fermented foods. Zygosaccharomyces rouxii can be isolated from fermenting soy sauce. An ascomycetous mold genus is used for fermentation; Monascus pilosus and Monascus purpureus are used for making rice wine and kaoling brandy, respectively. Other ascomycetes are occasionally used in fermentation.

Yeasts has a single-celled thallus. The thallus of most of these terrestrial fungi consists of a well-developed, septate, haploid mycelium that contains chitin in the cell wall. The ascomycete thallus grows under the substratum surface; only reproductive structures are exposed to the air.

3. Class Taphrinomycotina contains a single species that is pathogenic in humans: Pneumocystis jirovecii.

The hyphae of ascomycetes lack the dolipore septa and clamp connections of basidiomycetes; their septa have a single, central pore. Mobile organelles (microbodies) with dense protein cores, called Woronin bodies, plug the septal pores and isolate damaged hyphal compartments from the rest of the colony. These organelles are found in the largest subphylum, the Pezizomycotina, which contains 90% of the Ascomycota, but are absent from the other members of the phylum.

|

DIFFERENCE

BETWEEN ASCOMYCETES AND BASIDIOMYCETES |

|

|

ASCOMYCETES |

BASIDIOMYCETES |

|

They are sac fungi |

They are club fungi |

|

Septa possess simple central pores |

Septa have dolipores or pores with bracket–shaped

outgrowths |

|

Clamp connections do not occur |

Clamp connections occur between adjacent cells |

|

Primary mycelium well developed |

Primary mycelium is less developed |

|

Sex organs are common |

Sex organs are absent |

|

Karyogamy and meiosis occur inside an ascus |

Karyogamy and meiosis occur inside a basidium |

|

Ascospores are produced ascospores are produced

internally within the asci and released upon rupture |

Basidiospores are external, borne on the surface

of the basidia |

|

They are decomposers or coprophilous |

They are symbiotic or mycorrhizal |

|

Powdery colonies with striation |

White, woolly colonies that may emit an unpleasant

odor |

|

Inhibited by Benomyl |

Tolerant with Benomyl |

|

SEPTA

WITH WORONIN BODY |

SEPTA

WITH DOLIPORE |

|

|

|

THE BASIDIOMYCOTA

The Basidiomycota bear their sexual spores externally on a usually club-shaped structure called a basidium, which is often borne on or in a fruiting body called a basidiocarp or basidiome. This phylum includes the well-known mushrooms, both edible and poisonous, as well as boletes, puffballs, shelf fungi, jelly fungi, and coral fungi.

Basidiomycetes are the most potent degraders of cellulose because many species grow on dead wood and on forest or grass litter.

The phylum Basidiomycota is divided into three subphyla:

1. Agaricomycotina (fleshy basidiomycetes) – e.g., Cryptococcus neoformans, Trichosporon specie

a. The current classification defines two species: Cryptococcus neoformans, encompassing variety grubii (serotype A) and variety neoformans (serotype D), and Cryptococcus gattii (serotypes B and C).

The two species are also divided into eight major molecular types: VNI and VNII (variety grubii), VNIV (variety neoformans), VNIII (AD hybrids), and VGI – VGIV (Cryptococcus gattii).

Often referred to as the "sugar-coated killer," the protective polysaccharide (glucuronoxylomannan) capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans has been shown to be important in promoting infection. The polysaccharide capsule protects the cell from phagocytosis. Also, the melanization of cells reduces the surface charge and reduces the level of phagocytosis.

Cryptococcal urease activity is important for fungal propagation in the lungs as the enzyme promotes accumulation of immature dendritic cells as well as the nonprotective T2 immune response. Urease activity is also important in the fungus’ ability to cross the blood–brain barrier.

b. Trichosporon species is a yeast-like fungus macroscopically characterized by forming radially symmetrical colonies; these colonies may be white or yellowish, with a smooth texture, creamy, cerebriform, powdery or moist. Microscopically, Trichosporon species forms hyaline septate hyphae, with abundant arthroconidia and blastoconidia, and in some cases presents appressoria.

2. Ustilaginomycotina (smuts) – e.g., Malassezia furfur (aka Pityrosporum ovale). Other Malassezia species isolated from skin are: Malassezia restricta, Malassezia globosa, Malassezia dermatis, Malassezia arunalokei, Malassezia sloofiae, Malassezia sympodialis, Malassezia obtuse, Malassezia yamatoensis, Malassezia japonica.

All Malassezia species except for Malassezia pachydermatis are lipid dependent. Thus, Malassezia species require exogenous lipids to grow, making lipids a critical component of their growth. The high lipid content of Malassezia cell wall contributes to their mechanical stability, pathogenicity, resistance, and osmoresistance.

3. Pucciniomycotina

(yeasts

and filamentous fungi)

Method of reproduction:

1. Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction in basidiomycetes involves either budding or asexual spore formation. In the former, an outgrowth or bud appears and then separates from parent cell with the formation of transverse septum, yielding a new daughter cell. In the latter, asexual spore forms at the end of a specialized structure known as conidiophores and then breaks off and disperses.

2. Sexual Reproduction

Sexual reproduction in Basidiomycetes starts when a hypha of a primary mycelium (also called homokaryon, which has identical nuclei and usually develops upon the germination of a basidiospore) meets and fuses with a compatible monokaryotic hypha (typically of a different mating type) in a process known as plasmogamy (cytoplasmic fusion). As the two haploid nuclei remain separate in each cell, a secondary mycelium (also called heterokaryon) with dikaryotic hyphae (so called n + n hyphae), which carries two haploid nuclei in each cell, emerges. Under favorable environmental conditions, these dikaryotic hyphae form compact masses (called buttons) along mycelium, which grow into fruiting bodies (basidiocarps) made up of intertwined, matted hyphae (also called tertiary mycelium) that contain basidia (which are enlarged hyphal cells). The haploid nuclei then fuse in dikaryotic cells and become diploid zygote in a process known as karyogamy (nuclear fusion). Diploid zygote then undergoes meiosis and produces four haploid nuclei with different genotypes. Migration of the nuclei to the outer edge creates finger-like extensions in basidium, which turn into basidiospores (so called club fungi, because of their microscopic club-shaped basidia) after nuclei and some cytoplasm also move in. Subsequent formation of a septum (as well as clamp connection nearby, which controls the transfer of nuclei during cell division and maintains dikaryotic stage with two genetically different nuclei in each hyphal compartment) separates basidiospore from the rest of basidium. Following forcible discharge, the basidiospore germinates and produces a new primary mycelium.

THE DEUTEROMYCETES

The deuteromycetes, commonly called molds, are “second-class” fungi that have no known sexual state in their life cycle, and thus reproduce only by producing spores via mitosis. This asexual state is also called the anamorph state or imperfect state.

Despite its “–mycetes” suffix, the deuteromycetes are not a class; rather this term is now used as a common name for this dumping-ground group of fungi. It is an artificial grouping in that the phylogenetic relationships among taxa are mostly unknown or not apparent.

They are also known as the fungi imperfecti, because of their “imperfect” lack of sex. When the “perfect state” of one of these organisms is discovered, as happens every year, the fungus is more properly classified with the teleomorph name, although in practicality, like for people, it is difficult to remember to switch to their “married” name. Notice that this group is not classified as one of the phyla. It is just a loose assemblage of organisms that we have not been sure where to place accurately in the taxonomic order.

An example is the case of some dermatophytes, mostly the zoophilic and geophilic species of Microsporum and Trichophyton which can reproduce sexually and produce ascomata with asci and ascospores are classified as Ascomycetes. However, the same dermatophytes, in their anamorphic state in their human host are then placed under the Deuteromycetes, in the order Moniliales.

Although we can accurately place most of these fungi into phyla using molecular biology techniques such as PCR and DNA sequencing, mycologists maintain this group and its genera for convenience and tradition.

The group is characterized by the absence of teleomorphic (meiotic) states. It is heterogeneous, i.e., polyphyletic. Reproduction is commonly by spores (conidia) produced mitotically (asexually) from conidiogenous cells which are sometimes free (as in yeasts) or more commonly formed on separate supporting hyphae (conidiophores) and/or cells which may be produced in or on organized fruiting structures (conidiomata). Taxa are separated by differences in conidiogenous events, and the structures involved, conidiomatal form and development, conidial morphology, colony characteristics, and the presence and nature of vegetative structures.

Classification of Deuteromycetes:

1. Moniliales

– producing spores on simple conidiophores.

2. Sphaeropsidales

– producing spores in pycnidia.

3. Melanoconiales

– producing spores in acervuli.

4. Mycelia Sterilia or Agonomycetes – are fungi which usually produce neither sexual (meiotic) nor asexual (mitotic) spores.

THE OOMYCETE

Fifty years ago, the oomycetes were defined as “phycomycetes having oospores” and the Phycomycetes were at the same classification level as the ascomycetes and basidiomycetes within the Fungi. The cell walls of oomycetes are mainly composed of β-1,3-glucan polymers, and cellulose, and unlike fungal cell walls, contain little chitin.

Pythium insidiosum (formerly Hyphomyces destruens), belonging to the kingdom Stramenopila, is a fungus-like, aquatic oomycete found in tropical, subtropical, and temperate climates. It was long misrecognized as a fungus due to its fungus-like morphologic characteristics. The organism is not a true fungus and is classed in the kingdom Protista. It is a plant parasite that resides in stagnant water and releases motile zoospores that are attracted not only to plants but also to hair, especially to horses and some breeds of dogs. Infection is acquired through small wounds via contact with water that contains motile zoospores or other propagules (zoospores or hyphae). They are closely related to the algae, simply lacking chloroplast.

Depending on the site of entry, infection can lead to different forms of pythiosis i.e. a cutaneous, vascular, ocular, gastrointestinal and a systemic form, which is rarely seen. Unlike vascular pythiosis which mostly occurs in thalassemic patients, cutaneous and subcutaneous pythiosis can present in non-thalassemic and non-hematologic patients, predominantly in the agricultural population. Clinical manifestations of subcutaneous pythiosis resemble many fungal diseases such as entomopthoromycosis and mucormycosis.

The life cycle of Pythium insidosum starts from the development of undifferentiated sporangia which are then cleaved, and several biflagellate zoospores are released. The zoospores then swim and preferentially attach to plant and animal tissues. They subsequently become encysted zoospore which then elongate their germ tubes to penetrate and assist their hyphae’s invasion into the host tissues.

Classification of Mycotic Infections:

For a fungus to infect humans, it must fulfill four criteria: (1) thermal resistance, (2) locomotion through or around host barriers, (3) lysis and absorption of human tissue, and (4) resistance to immune defenses.

1. Superficial,

cutaneous or dermatomycoses

2. Subcutaneous

mycoses

3. Systemic

or deep mycoses

4. Opportunistic

infections

SUPERFICIAL MYCOSES

Skin infection of Fungal origin can be classified as:

1. Dermatophytes

2. Epidermomycoses

3. Trichomycosis or Trichobacteriosis

THE DERMATOPHYTES

One characteristic of the dermatophytes is their ability to utilize keratin in epidermal tissues. Dermatophytes infect the epidermis and adnexal structures, including hair follicles and hair shafts, inducing pruritus, patchy alopecia, erythema, and crusting. In general, dermatophytes can degrade skin keratin tissue by secreting a large number of hydrolases, and then invade the keratin layer through adhesion, germination, invasion, and infiltration.

Dermatophytes can be classified into five genera, namely Arthroderma, Epidermophyton, Microsporum, Nannizzia, and Trichophyton. Arthroderma and Microsporum are both zoophilic dermatophytes.

Most skin fungi can adapt to a temperature like that of the skin surface (26°C) and cannot grow well at body temperature (37°C). Therefore, the internal temperature of the body exerts a certain protective effect against skin fungal infections becoming systemic.

A dermatophytid or mycid is a secondary, distant, hypersensitive reaction that can occur as immunological response to a dermatophyte infection. The essential criteria for diagnosis are: (1) a proven focus of dermatophyte infection confirmed by fungal isolation in culture; (2) absence of dermatophyte isolation from the dermatophytid lesion, and (3) clearing of dermatophytid lesion after dermatophyte has been eradicated.

|

CLASSIFICATION

OF DERMATOPHYTES |

|||

|

Classification |

Primary

Host |

Species |

Infection |

|

Anthropilic |

Humans |

Epidermophyton floccosum |

Tinea cruris (Jock itch or Dhobie itch) |

|

Humans |

Trichophyton rubrum |

Tinea pedis (Athlete’s Foot), Tinea unguium

(Onychomycosis), Tinea cruris, Tinea faciei, Tinea corporis, Tinea manuum,

Tinea barbae |

|

|

Humans |

Trichophyton tonsurans |

Tinea capitis, Tinea corporis, Tinea faciei |

|

|

Humans |

Trichophyton digitale |

Tinea pedis |

|

|

Humans |

Trichophyton schoenleinii |

Tinea capitis favosa (Favus honeycomb) |

|

|

Humans |

Trichophyton concentricum |

Tinea imbricata or Tokelau |

|

|

Zoophilic |

Cats |

Microsporum canis |

Ringworm |

|

Voles, bats |

Nannizzia persicolor |

Ringworm (formerly

Arthroderma persicolor) |

|

|

Pigs |

Nannizzia nana |

Ringworm (formerly

Microsporum nanum) |

|

|

Horses |

Trichophyton equinum |

Ringworm |

|

|

Mice, guinea pigs |

Trichophyton mentagrophytes |

Ringworm (formerly

Arthroderma vanbreuseghemii) |

|

|

Cattle |

Trichophyton verrucosum |

Ringworm |

|

|

Geophilic |

Soil |

Nannizzia gypsea |

Ringworm (animals), Tinea capitis / Tinea corporis (humans) |

|

DIAGNOSTIC

CHARACTERISTICS OF DERMATOPHYTES |

||

|

Dermatophyte |

Cultural

characteristic |

Microscopic

characteristic |

|

Trichophyton rubrum |

White colony with downy to velvety texture, and

red reverse pigment |

Delicate pyriform to claviform microconidia and

cigar-shaped macroconidia |

|

Trichophyton mentagrophytes |

White to beige colony with powdery surface, brown

reverse pigment |

Clustered round microconidia, spiral hyphae, and

claviform macroconidia |

|

Trichophyton tonsurans |

Beige colony with velvety to powdery texture,

radial grooves, and reddish-brown reverse pigment |

Long claviform to broad pyriform microconidia,

cigar-shaped macroconidia, and clamidoconidia |

|

Epidermophyton floccosum |

Beige velvety colony raised and folded in the

center, yellowish-brown reverse pigment |

Thin-walled macroconidia growing directly from the

hyphae and numerous clamidoconidia |

|

Microsporum canis |

White colony with fuzzy texture, bright golden

yellow reverse pigment |

Spindle-shaped, thick-walled macroconidia with

more than 6 cells, and few pyriform to claviform microconidia |

|

Nannizzia gypsea |

Beige colony with granular texture, brown reverse

pigment |

Ellipsoidal, thin-walled, four to six-celled

macroconidia, and numerous claviform microconidia |

THE EPIDERMOMYCOSES

The epidermomycosis are superficial mycosis which affects the epidermis and present three clinical forms: epidermis of the hairless skin, intertrigo, and palmoplantar keratoderma.

1. Malassezia furfur

Malassezia furfur is an anthropophilic fungus that belongs to the physiological skin flora. The fungus can grow in a yeast phase as well as in a mycelial phase; on nonaffected skin the fungus is mainly prevalent in the yeast phase. The organism has complex lipid requirements for growth, which also explains its occurrence on the skin. The infection is known as Pityriasis versicolor.

Clinical features of pityriasis versicolor include either hyperpigmented or hypopigmented finely scaled macules. The most frequently affected sites are the trunk, neck, and proximal extremities.

Seborrheic dermatitis is caused by a non-specific immune response to Malassezia species, which triggers an inflammation in seborrheic areas such as the scalp, face, chest, back, axilla, and groin.

2. Hortaea werneckii

Hortaea werneckii (formerly known as Phaeoannellomyces werneckii, Exophiala werneckii, and Cladosporium werneckii) is the etiologic agent of tinea nigra, a superficial cutaneous mycosis typically involving either the palms of the hands or soles of the feet.

Tinea nigra typically occurs in children and young adults, with female predominance. It is observed in patients living in warm countries and in those who have lived in or visited the tropics or subtropics.

Tinea nigra is clinically characterized by a sharply marginated, light brown to black, nonscaly, oval-shaped macule. In some patients, this macule is mottled and might be irregular in shape. The lesion is usually single and asymptomatic. It is mainly observed on the palmar surface. However, involvement of the plantar surface, neck, or trunk can also occur.

3. Corynebacterium minutissimum

Erythrasma caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum is a common disease, occurring more often in men and with a predilection for the intertriginous areas. The organism possesses keratolytic properties and lesions cause thick lamellated plaques on affected areas. The toe web spaces are commonly affected. In Wood's lamp examination, it reveals a striking bright coral red–pink fluorescence.

Corynebacterium minutissimum is a gram-positive bacillus and was added on the list as it can have coinfection with other Dermatophytes and is the only bacteria which responds to Wood's lamp.

THE TRICHOMYCOSES OR TRICHOBACTERIOSIS

Trichomycoses are diseases of the hair caused by fungi. It usually affects the axilla or pubic region. Trichomycosis is a misnomer, and a more correct term would be trichobacteriosis or bacterial trichonodosis which is a superficial infection, primarily of the axillary hair, which can exhibit three different clinical presentations: The most common clinical variant is trichomycosis flava (yellow), while rubra (red) and nigra (black) variants occur much less frequently.

Corynebacterium flavescens (formerly Corynebacterium tenuis)

Trichomycosis axillaris (or trichobacteriosis) is a superficial bacterial infection of the soft keratin of hair located in the armpit, pubis or, less commonly, the scrotum or scalp. It is often associated with poor hygiene, obesity, and hyperhidrosis.

Corynebacterium flavescens (Corynebacterium tenuis) is the causative agent for this condition and hence the traditional name trichomycosis axillaris, which implies a fungal infection, is a misnomer. The most common sign of trichomycosis axillaris is the presence of red-stained perspiration on the clothing, and individuals with hyperhidrosis often complain of a particularly offensive axillary odor. A bacterial biofilm encases the hair, creating yellow or white concretions distributed along the length of the hair shaft.

Click here for full discussion on Corynebacterium.

Other Superficial Mycoses:

1. Trichosporon specie

White piedra is an uncommon infection caused by yeasts of the genus Trichosporon, namely, Trichosporon ovoides (scalp hair), Trichosporon inkin (pubic hair), and Trichosporon asahii (rare in piedra). It is a superficial infection of the hair shafts of the scalp, body, or pubic hair. Trichosporon species may also cause a systemic infection in neutropenic patients.

The organisms may be carried on the skin or around the anus. In some patients, the infection appears to be sexually transmitted. White piedra is asymptomatic and manifests as small yellow concretions on the hair shafts. The pathogenesis of this infection is still unclear, but it is likely to result from synergy between the fungi and coryneform bacteria. The lesions are circumscribed and appear as small nodules, unlike the more diffuse coating of axillary or pubic hair seen in trichomycosis axillaris, which is caused by the presence of bacteria on the hair.

Cultures

obtained from diverse clinical samples are used for identifying the etiologic

agent through its microscopic morphology by confirming the presence of the 3

characteristic structures of the genus Trichosporon: hyphae, arthrocondia, and

blastocondia.

2. Piedraia hortae

Black piedra is a fungal infection of the hair shafts of humans and animals.

The clinical presentation is the finding of multiple 1–2 mm hard, darkly pigmented oval nodules adherent to hair shafts. Infection is normally restricted to scalp hair but may involve hair at any site. Multiple nodules may be present on a single hair, weakening the hair shaft and possibly resulting in breakage. Patients do not experience pruritus and they are otherwise asymptomatic apart from the cosmetic effects of the nodules.

SUBCUTANEOUS MYCOSES

It involves the skin and subcutaneous tissue, generally without dissemination to the internal organs of the body. Infection is through inoculation of spores into cutaneous and subcutaneous after trauma.

1. Sporotrichosis (Gardener’s disease) is a chronic granulomatous mycotic infection caused by Sporothrix schenckii, a common saprophyte of soil, decaying wood, hay, and sphagnum moss, that is endemic in tropical/subtropical areas. It is classified as a primary cutaneous disease, with three different clinical presentations: lymphocutaneous, fixed, and disseminated. Extracutaneous disease includes osteoarticular, which is the most common, pulmonary, mucosal, or systemic. It is an occupational hazard among florists, miners, farmers, and others working in with soil.

Sporothrix schenckii has the dimorphic ability that it remains as a yeast-like form at a temperature between 35°C and 37°C and converts into a mycelial phase (with branching, septate hyphae) at a temperature range between 25°C and 30°C. This nature helps it to survive in the environment and becomes pathogenic in animals. It can synthesize melanin.

2. Phaeohyphomycosis refers to infections caused by many kinds of dark, melanin-pigmented dematiaceous fungi that appear in tissue as septate hyphae, as pseudohyphal cells, as catenulate cells (toruloid hyphae), as yeast-like cells, or as any combination of these forms. It is distinguished from chromoblastomycosis and mycetoma by the absence of specific histopathologic findings. Mycetoma and phaeohyphomycosis result in tissue necrosis, whereas chromoblastomycosis infections lead to excessive proliferation of host tissue. Infection results from traumatic implantation. Most cases occur in immunocompetent individuals and are common in tropical and subtropical climates. Dematiaceous molds are also important causes of invasive sinusitis and allergic fungal sinusitis.

3. Chromomycosis or chromoblastomycosis or CBM (also known as chromomycosis, Carrión mycosis, Lane–Pedroso mycosis, verrucoid dermatitis and black blastomycosis) is a term that describes a group of chronic localized infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, most often involving the limbs. It is characterized by raised crusted lesions as a result of excessive proliferation of host tissue. It is caused by traumatic inoculation of the skin with a number of brown pigmented (dematiaceous) molds. In tissue, the fungi basically occur as large, muriform, thick-walled dematiaceous cells. The presence of “copper pennies” known as Medlar bodies are diagnostic of the infection. It forms a warty, tumor-like lesion resembling cauliflower.

The great majority of patients are inhabitants of rural areas (farmers, wood cutters, latex gatherers), between 35 and 50 years of age. Men are more affected than women and the lesions are usually on the lower limbs.

The etiologic agents include Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Fonsecaea compacta, Phialophora verrucosa, Cladosporium carrionii and Cladosporium ajello, Botriomyces caespitosus and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa. Newer agents include Exophiala jeanselmiei and Exophiala spinifera. Fonsecea pedrosoi is the commonest agent of chromoblastomycosis and the uncommon agents are Cladosporium and Rhinocladiella species.

4. Mycetoma is a chronic suppurative infection affecting skin, subcutaneous tissue, and bones prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions. It is a disorder of subcutaneous tissue, skin, and bones, mainly of feet, characterized by a triad of localized swelling, underlying sinus tracts, and production of grains or granules. Mycetoma is usually localized but may extend slowly by direct contiguity along the fascial planes, invading the subcutaneous tissue, fat, ligaments, muscles, and bones.

Etiological classification divides Mycetoma into:

a. Eumycetoma – caused by fungus. It is a suppurative and granulomatous subcutaneous fungal infection, most often affecting the lower extremity. It is usually confined to the subcutaneous tissues but may extend to involve underlying fascia, bone, and, rarely, regional lymph nodes via contiguous dissemination. Infection usually presents painless nodules that progress to form sinuses that drain out pus and aggregated fungi that are seen macroscopically as grains. It is also known as fungal tumor.

b. Actinomycetoma – caused by bacteria and characterized by both osteolytic and osteosclerotic lesions. The result is gross swelling of the affected part with deformity. Actinomycetoma tends to progress more rapidly, with greater inflammation and tissue destruction and earlier invasion of bone than implantation mycosis.

|

TYPE |

Agent |

Grain

Color |

|

ACTINOMYCOTIC |

Nocardia

asteroides |

White |

|

Nocardia brasiliensis |

White |

|

|

Nocardia otitidiscaviarum |

White |

|

|

Actinomadura madurae |

White |

|

|

Actinomadura pelletieri |

Red to pink |

|

|

Streptomyces somaliensis |

White to yellow |

|

|

EUMYCOTIC |

Madurella mycetomatis |

Black to brown |

|

Madurella grisea |

Black to brown |

|

|

Leptosphaeria senegalensis |

Black |

|

|

Curvularia lunata |

Black |

|

|

Neotestidina rosattii |

Yellow |

|

|

Acremonium species |

White to yellow |

|

|

Fusarium species |

White to pale yellow |

|

|

Scedosporium apiospermum |

White to pale yellow |

Click here for full discussion of Actinomycetoma

5. Conidiobolomycosis is a rare chronic subcutaneous mycosis of nose, and paranasal sinuses predominately affects the middle-aged men in tropical countries. It is caused by a saprophytic fungus “Conodiobolus coronatus,” which can survive in soils and dried vegetables for long period of time. It is a fungus composed of thick-walled, short hyphae that grows at temperatures of 30 to 37oC. In “Conidiobolus” infection the nasal mucosa below the inferior turbinate is predominantly affected and appears as a uniform nasal swelling forming a centrofacial deformity.

6. Basidiobolomycosis is a subcutaneous fungal infection caused by “Basidiobolus ranarum” which develops following traumatic inoculation of the fungus under the skin of limb or limb girdle areas, mostly in the children.

7. Lobomycosis or Lacaziosis, also known as keloidal blastomycosis or Jorge Lobo disease, is caused by the fungus Lacazia loboi. The infection is restricted to tropical areas of Central and South America and is hyperendemic in areas of Brazil. The organism is known to cause disease in humans and in dolphins.

The infection occurs mainly in men from rural areas who work in close contact with vegetation and aquatic environments. The disease is limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissues, except for the possibility of lymph node involvement.

8. Phythiosis is a cutaneous disease caused by invasion of the organism Pythium insidiosum, a fungus-like oomycete. The disease occurs principally in warm, tropical regions; the organism has an aquatic life cycle and requires relatively warm temperatures for reproduction. Characteristic lesions are ulcerative masses of granulation tissue. Rapid enlargement can occur, even within a matter of days. Pythiosis is often pruritic; sinus tracts are visible and often contain gritty, coral-like masses, called “kunker” or “leeches.” In chronic, untreated infections, invasion of deeper tissues, including bone, joints, tendon sheaths, and lymph nodes, can occur. Majority of the previously reported cases of cutaneous and subcutaneous pythiosis were strongly associated with water exposure.

Functional properties of fungal melanin:

1. Structural

enforcement (cell walls) against osmotic and turgor forces

2. Desiccation

protection

3. Thermal

stress protection

4. Protection

against ionizing radiation (UV, γ-radiation etc.)

5. Salt

and pH stress protection

6. Mopping

up heavy toxic metals

7. Antioxidant

8. Protection

against lytic enzymes

9. Fending

off microbial attacks

10. Enhancing

virulence of plant pathogens

11. Converting

radioactive and other radiation to energy for metabolic processes

SYSTEMIC MYCOSES

Systemic fungal diseases are primary pulmonary diseases caused by the dimorphic fungal pathogens. They predominantly affect people with immunocompromising conditions.

Dimorphic fungi are organisms that can switch between two morphologies during their lifecycle: yeast and hyphae. In thermal-dimorphic fungi, morphologic changes are induced by temperature.

1. Blastomyces dermatidis (asexual stage is Ajellomyces dermatitidis)

a. The infection is called Blastomycosis or Gilchrist disease.

a. Chronic infection is found mainly in the lungs. It resembles tuberculosis.

b. Dimorphic fungus

(1) Yeast

phase (37oC) – single bud with broad base

(2) Filamentous phase – numerous septate, slender conidiophore with round conidia

2. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii

a. The infection is called South American Blastomycosis or Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) or Paracoccidioidal granuloma.

a. A chronic granulomatous disease of the skin, mucous membranes, lymph nodes and internal organs. The disease is most often seen in middle-aged to elderly men who live in rural areas.

b. Dimorphic fungus

(1) Yeast

phase (37oC) – multiple budding resembling “pilot wheel.”

(2) Filamentous phase – similar to Blastomyces dermatidis

3. Histoplasma capsulatum (asexual stage is Ajellomyces capsulatus)

a. The infection is called Histoplasmosis or Darling’s disease.

b. Histoplasma taxonomically has been divided into three groups based on geographic distribution and clinical manifestations: variety capsulatum which is the most common worldwide, variety duboisii found in Africa, and variety farciminosum known to be a horse pathogen.

c. The fungus thrives in damp soil that's rich in organic material, especially the droppings from birds and bats. The mildest forms of histoplasmosis cause no signs or symptoms. But severe infections can be life-threatening. When signs and symptoms occur, they usually appear in 3 to 17 days. The most severe variety of histoplasmosis occurs mainly in infants and in people with weakened immune systems called disseminated histoplasmosis, it can affect nearly any part of your body, including your mouth, liver, central nervous system, skin, and adrenal glands.

d. Dimorphic fungus

(1) Yeast

phase (37oC) – uninucleated budding cell

(2) Filamentous phase – tuberculate chlamydospores (infective stage)

4. Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii

a. The infection is called Coccidioidomycosis

b. It forms a hypersensitivity reaction in the form of erythema nodosum called Valley Fever or Desert rheumatism. Coccidioidomycosis is typically a self-limiting influenza-like respiratory illness; however, it can lead to disseminated disease outside of the lungs. Coccidioidal meningitis is a granulomatous infection of the brain and is the most lethal manifestation of coccidioidal infection.

c. Dimorphic fungus

(1) Yeast

phase (37oC) – spherules filled with endospores

(2) Filamentous phase – arthrospores (highly infectious)

5. Emergomyces canadensis and Emergomyces africanus

a. The infection is called Emergomycosis (formerly disseminated emmonsiosis).

b. It is common in HIV–positive persons with low CD4 lymphocyte count and has an estimated fatality of 50%. The infection exhibits airborne transmission with pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations leading to skin lesions manifesting as verrucous lesions, papules, plaques, nodules, or ulcers that are widespread.

c. Dimorphic fungus

(1) Yeast

phase (37oC) – Thin-walled, round-to-ovoid yeast cells measuring 3–6

μm in diameter with narrow-neck budding

(2) Filamentous phase – slender conidiophores that arise from hyphae at right angles and form “florets” of short secondary conidiophores bearing single small subspherical conidia.

6. Talaromyces marneffei

a. The infection is called Talaromycosis (Penicilliosis)

b. It is a primary lung pathogen that disseminates to other internal organs by lymphatic or hematogenous mechanisms. It causes disseminated disease in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, though it is most prevalent in patients with HIV/AIDS as well as patients with functional impairments of cellular immunity, particularly defects in CD4 T cell activity. Talaromycosis is frequently observed in advanced stages of HIV infection with CD4 counts below 100 cells/µL and even more frequently when CD4 counts are less than 50 cells/µL.

c. Talaromyces marneffei can grow with yeast at 37°C, and therefore, can resist body temperature stress. Moreover, it can tolerate the phagocytosis mechanism, surviving and replicating within the macrophage, then escaping into the cytoplasm.

d. Dimorphic Fungus

(1) Yeast

phase (37oC) – spherical to ellipsoidal, 2-6 µm in diameter

(2) Filamentous phase – greenish yellow to yellow conidia and secretes a characteristic diffusible red pigment.

OPPORTUNISTIC MYCOSES

Opportunistic fungal infections are caused by fungi that are nonpathogenic in the immunocompetent host but may cause infection in immunocompromised hosts. They oftentimes cause pulmonary infection.

1. Candida albicans

Candida species are part of the normal flora, and disease usually occurs after physical trauma, including surgery, or biochemical imbalance altering the microenvironment in which the fungus resides. The morbidity and mortality rates for candidiasis are alarmingly high, and the progression of the disease has a fatal prognosis of up to 80%, even after the commencement of treatment. It is acute or chronic, superficial, or disseminated mycosis.

Candida albicans appears in several morphological forms (blastospores, pseudohyphae, and hyphae). Candidalysin is a cytolytic 31-amino acid α-helical amphipathic peptide produced by the Candida albicans hyphae, and it is crucial in damaging the host cells.

a. Thrush or Candidiosis or Candidiasis – a disease of oral mucous membrane and is characterized by the formation of white creamy patches seen most often on the tongue.

(1) Pseudomembranous candidosis is the most common form and is characterized by white patches or plaques on the oral mucosa that can be easily detached by gentle scraping, because only the upper layer of the mucosal epithelium is infected. The possibility of removal is an accepted differential diagnostic feature that distinguishes this form of candidosis from other white accumulations in the mouth. It typically occurs in neonates (who are likely to become infected through the birth canal), anemic, and immunodeficient individuals (HIV, diabetes, malignancy), patients on topical steroid therapy, and those with xerostomia.

(2) Acute erythematous or atrophic candidosis occurs as a side-effect of systemic therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics and immunosuppressants and corticosteroids, consequently altering the oral cavity’s flora. It is clinically manifested as a painful red lesion on the dorsum of the tongue, and depapilation of the tongue is often present, with symptoms of burning and taste changes.

(3) Chronic erythematous or atrophic candidosis is also known as denture stomatitis or prosthetic palatitis. It is typical for patients who wear mobile acrylic prosthetic replacements and is most commonly found on the palate in people with total dentures. The onset of the disease is facilitated by poor oral hygiene and inadequate hygiene of the dentures. Lesions on the mucosa are red and limited to areas covered by the prosthetic replacement, sometimes accompanied by a burning sensation, but often are asymptomatic and detected only by dental examination.

(4) Chronic hyperplastic candidosis is also called Candida leukoplakia. Unlike the pseudomembranous form, these white deposits cannot be removed by light scraping. It is characterized by deep infiltration of the oral cavity tissue by the hyphae of the fungus. Most commonly, it is found on the lateral parts of the tongue and buccal mucosa. Clusters may be homogeneous or heterogeneous. Heterogeneous lesions are precancerous conditions because they are a predisposing factor for malignant transformation.

(5) Angular cheilitis is an inflammatory condition of one, or more often, both corners of the lips and is clinically manifested by redness, erosions, and crusts that are sometimes covered with white plaque.