The classical taxonomic classification divided the Protozoa into four groups:

a. Sarcodina

(amoebae)

b. Mastigophora

(flagellates)

c. Sporozoa

(most parasitic protozoa)

d. Infusoria (ciliates)

This taxonomy has been totally abandoned by the International Society of Protozoologists based on modern morphological approaches such as biochemical pathways and molecular phylogenetics (e.g., 18S rRNA sequences). The older hierarchical systems consisting of the traditional “kingdom,” “phylum,” “class,” “subclass,” “super-order,” “order,” has been replaced by a new vocabulary.

According to this new schema, the Eukaryotes have been classified into six clusters or “Super Groups,” namely:

a. Amoebozoa

b. Opisthokonta

c. Rhizaria

d. Archaeplastida

e. Chromalveolata

f. Excavata

The three amoebae that are dealt within this article have been classified under two Super Groups, Amoebozoa and Excavata, as follows:

a. Acanthamoeba and Balamuthia are classified under Super Group Amoebozoa: Acanthamoebidae

b. Naegleria fowleri under Super Group Excavata: Heterolobosia: Vahlkampfiidae

This schema has been proposed as the basis for future revisions.

For

educational purposes, the classic phylogeny of the parasite was described here.

And unlike amoeba belonging to Phylum Sarcodina that requires host to survive,

parasites belonging in this group are free living (i.e., doesn’t require host

to survive).

NAEGLERIA FOWLERI

Phylum

Percolozoa

Subphylum

Tetramitia

Order

Schizopyrenida

Family

Vahlkampfiidae

Genus Naegleria

Naegleria fowleri is an amphizoic amoeba, as it can survive in a free-living state in water, soil, or in the host, which can be the human central nervous system (CNS) and causes a disease known as Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) thus its reputation as "brain-eating amoeba."

The initial symptoms of PAM are indistinguishable from bacterial meningitis, while the symptoms of GAE can mimic a brain abscess, encephalitis, or meningitis.

The amoeboid stage is roughly cylindrical, typically around 20–40 μm in length. They are traditionally considered lobose amoebae, but are not related to the others, and unlike them, do not form true lobose pseudopods. Instead, they advance by eruptive waves, where hemispherical bulges appear from the front margin of the cell, which is clear. The flagellate stage is slightly smaller, with two or four anterior flagella anterior to the feeding groove.

Naegleria fowleri has been thought to infect the human body by entering the host through the nose when water is splashed or forced into the nasal cavity. Infectivity occurs first through attachment to the nasal mucosa, followed by locomotion along the olfactory nerve and through the cribriform plate (which is more porous in children and young adults) to reach the olfactory bulbs within the CNS. Once Naegleria fowleri reaches the olfactory bulbs, it elicits a significant immune response through activation of the innate immune system, including macrophages and neutrophils. Naegleria fowleri enters the human body in the trophozoite form. Structures on the surface of trophozoites known as food cups enable the organism to ingest bacteria, fungi, and human tissue. In addition to tissue destruction by the food cup, the pathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri is dependent upon the release of cytolytic molecules, including acid hydrolases, phospholipases, neuraminidases, and phospholipolytic enzymes that play a role in host cell and nerve destruction. The combination of the pathogenicity of Naegleria fowleri and the intense immune response resulting from its presence results in significant nerve damage and subsequent CNS tissue damage, which often result in death.

The quickest way to diagnose Naegleria fowleri infection is by microscopic examination of fresh, unfrozen, unrefrigerated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Both

chlorinated and salt water significantly decrease the risk of Naegleria fowleri

infection due to its inability to survive in such environments. Thus, avoidance

of exposure to freshwater bodies such as lakes, rivers, and ponds, especially

during the summer months when the water temperature is higher.

ACANTHAMOEBA

SPP.

Phylum

Amoebozoa

Class

Conosea

Order

Centramoeba

Family Acanthamoeba

Some of the pathogenic species:

a. Acanthamoeba

castellanii

b. Acanthamoeba

culbertsoni

c. Acanthamoeba

polyphaga

d. Acanthamoeba

healyi

e. Acanthamoeba divionensis

Diseases caused by Acanthamoeba include keratitis and granulomatous amoebic encephalitis (GAE).

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is associated with trauma to the cornea or contact-lens wear and the use of amoeba–contaminated saline. Minor erosion of the corneal epithelium may occur while wearing hard or soft contact lenses, and the subsequent use of contaminated saline solution is the major risk factor for Acanthamoeba keratitis. AK is characterized by inflammation of the cornea, severe ocular pain, and photophobia, a characteristic 360o or paracentral stromal ring infiltrate, recurrent breakdown of corneal epithelium, and a corneal lesion refractory to the commonly used antibiotics. Typically, only one eye is involved; however, bilateral keratitis has also been reported. It is the MBP (mannose binding protein) that mediates the adhesion of the amoeba to corneal epithelial cells and is central to the pathogenic potential of Acanthamoeba.

A unique and characteristic feature of Acanthamoeba spp. is the presence of fine, tapering, thorn-like acanthopodia that arise from the surface of the body.

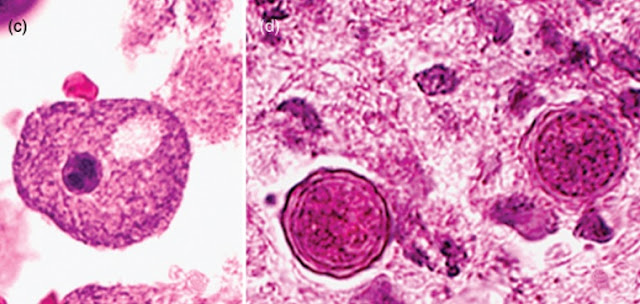

a. The trophozoites range in size from 15 to 50mm depending upon the species. They are uninucleate, and the nucleus has a centrally placed, large, densely staining nucleolus. The cytoplasm is finely granular and contains numerous mitochondria, ribosomes, food vacuoles, and a contractile vacuole. When food becomes scarce, or when it is facing desiccation or other environmental stresses, the amoebae round up and encyst.

b. Cysts are double-walled and range in size from 10 to 25mm. Cysts are uninucleate and possess a centrally placed dense nucleolus. Upon return to favourable growth conditions, the dormant amoeba is activated to leave the cyst by dislodging the operculum and reverting to a trophic form

(1) The outer cyst wall, the ectocyst, is wrinkled with folds and ripples and contains protein and lipid.

(2) The inner cyst wall, the endocyst, contains cellulose and hence is Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) positive. The endocyst varies in shape: it may best ellate, polygonal, oval, or spherical.

(3) Pores or ostioles that are covered by convex–concave plugs or opercula are present at the junction of the ectocyst and the endocyst.

In either the trophic or the cyst stage these organisms have a wide distribution in nature, and it is virtually impossible not to isolate members of this genus from soil, water, and other samples.

Acanthamoeba spp. Are ubiquitous and occur worldwide. They have been isolated from soil, fresh and brackish waters, bottled mineral water, cooling towers of electric and nuclear power plants, heating, ventilating and air conditioning units, humidifiers, Jacuzzi tubs, hydrotherapy pools in hospitals, dental irrigation units, dialysis machines, dust in the air, bacterial, fungal and mammalian cell cultures, contact-lens paraphernalia, ear discharge, pulmonary secretions, swabs obtained from nasopharyngeal mucosa of patients with respiratory complaints as well as of healthy individuals, maxillary sinus, mandibular autografts, and stool samples. In addition, several Acanthamoeba species have been isolated from the brain, lungs, skin, and cornea of infected individuals.

BALAMUTHIA MANDRILLARIS

Balamuthia mandrillaris is a free-living amoeba that is found in the soil and fresh water and is associated with Granulomatous Amoebic Encephalitis (GAE), a “brain-eating” disease both in humans and animals. Symptoms of granulomatous amebic encephalitis begin gradually. Confusion, headache, and seizures are common. People may have a low-grade fever, blurred vision, changes in personality, and problems with speaking, coordination, or vision. One side of the body or face may become paralyzed.

Balamuthia mandrillaris may cause skin sores in addition to the symptoms above. Most infected people die, usually 7 to 120 days after symptoms begin.

Possible modes of transmission of Balamuthia include inhalation and inoculation through broken skin.

Balamuthia mandrillaris, like Acanthamoeba, has only two life-cycle stages, namely the vegetative trophozoite and the dormant cyst.

a. The trophozoite is pleomorphic and measures from 12 to 60 µm (mean of 30 µm). The trophic amoebae are usually uninucleate, although binucleate forms are occasionally seen. The nucleus contains a large, centrally placed, dense nucleolus; occasionally, however, amoebae with two or three nucleolar bodies have been seen, especially in infected tissues.

b. Cysts

are also uninucleate, are spherical, and range in size from 12 to 30 µm (mean

of 15 µm). Cysts, when examined with a light microscope, appear to be double

walled, the outer wall being wavy and the inner wall round, and pores are not

seen in the wall. Ultrastructurally, however, the cyst wall has three layers:

(1) an

outer thin and irregular ectocyst,

(2) an

inner thick endocyst, and

(3) a middle amorphous fibrillar mesocyst.

In general, Acanthamoeba spp. and Balamuthia are difficult to differentiate in tissue sections by light microscopy because of their similar morphology. However, they can be differentiated by immunofluorescence analysis of the tissue sections using rabbit anti–Acanthamoeba or anti–B–mandrillaris sera.

While Balamuthia and Naegleria share some similarities, Balamuthia is more difficult to detect. This is due to its resemblance to histiocytes under the microscope and unique culture requirements. Unlike Naegleria, Balamuthia cannot be grown on agar because it only feeds on mammalian cells and other amoebas. Furthermore, healthy individuals can be seropositive for Balamuthia antibodies due to the amoeba’s pervasive presence in the environment, while those with GAE show low titers. Additionally, cerebrospinal fluid analysis rarely demonstrates the organism, and the time course for the appearance of lesions and the onset of GAE is inconsistent. Balamuthia, unlike most of other free-living amoebae, does not feed on Gram-negative bacteria and therefore the use of non-nutrient agar coated with bacterial cultures has resulted to be ineffective for its growth.

These amoebae were normally cultured on monolayers of African green monkey kidney cells. Upon axenic cultivation, amoebae grew at various temperatures ranging from 25°C to 37°C (optimal growth at 37°C) and remained viable for up to several months, but they became smaller over time. In contrast, mammalian cultures can be used persistently as feeder cells to culture Balamuthia amoebae over longer periods, without any modifications in their general appearance. All tested cell cultures, including human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMEC), human lung fibroblasts, monkey kidney (E6) cells, and African green monkey fibroblast-like kidney (Cos-7) cells, supported the growth of B. mandrillaris.

No comments:

Post a Comment